The completion of a 10-day Oregon trip left me with a few more thoughts on Meriwether Lewis and William Clark and their 35-member Corps of Discovery.

The explorers and their group encountered aggressive grizzly bears, angry rivers, ravenous mosquitoes, hostile natives and towering mountains in their 1804 journey from their Illinois camp to the Pacific Ocean near Astoria, but I know how they feel. I experienced a nine-minute delay on one of my flights and the Starbucks line at the airport was too long for me to grab a cup of coffee without missing my initial plane.

We all have our trials and tribulations, right?

My five-person corps of discovery made it to Astoria from Portland (a grueling two-hour drive with a stop at a gas station that had only one restroom), and while the shoppers in the group raised their eyebrows at my interest in visiting the site of Fort Clatsop (five miles away) which the real Corps built to spend the winter, I managed to drag two reluctant travelers along with me. They left wearing “Lewis and Clark National Historic Park” so I think they were glad I did.

Before I get too far into this, here’s the backstory:

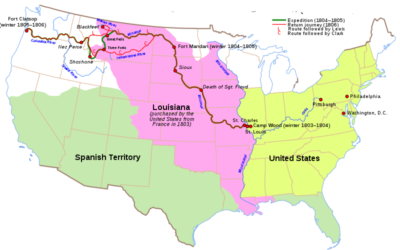

Lewis and Clark originally camped on the north shore of the Columbia River (in modern Washington) after a brutal November journey in storms, high wind and high waves that pounded them and beat them back for several days. They found their camp near the ocean insufficient; it had little game and the prolonged dampness that rotted their clothes. Clark didn’t like the seacoast – “salt water I view as an evil” – and visiting Indians said game was more plentiful on the southern shore.

In Clark’s words, there was also this:

“the sea which is immediately in front roars like a repeeted roling thunder and have rored in that way ever since our arrival in its borders which is now 24 days since we arrived in sight of the Great Western Ocean, I cant say Pasific as since I have seen it, it has been the reverse.”

So, Clark led a scouting team that found a swampy lowland with a pine forest that had so many elk that his group wouldn’t be in danger of starving to death over the winter. He chose a site two miles up a creek that today is called the Lewis and Clark River with access to a clearwater spring and some shelter from the weather. It was south of the Columbia and a few miles inland from the coast; the group moved there on December 7 and commenced building their winter quarters, which they called Fort Clatsop after one of the local tribes.

The “fort” has been rebuilt, and is the star attraction of the Lewis and Clark National Historic Park that includes numerous sites in both Oregon and Washington, some as far as 45 minutes away. It’s the star both because it’s in a beautiful spot surrounded by towering pines and because the explorers’ journals offer daily detail of life here. Any visitor who has read them – and all of those I encountered in the visitors’ center had all read at least some – can’t help but look at these cramped quarters and think about how uncomfortable it must have been.

And then again, if you examine this little log fort and compare it to the accommodations the Corps had experienced in the previous 18 months, a cold, damp, cramped room is still. . . a room.

The relentless weather didn’t help things. After the passage of winter, Clark noted that there had been only 12 days without rain and only six with sunshine. In his log for December 25, he wrote this:

“we would have Spent this day the nativity of Christ in feasting, had we anything to raise our Spirits or even gratify our appetites, our Diner consisted of pore Elk, so much Spoiled that we eate it through necessity, Some Spoiled pounded fish and a few roots.”

Merry Christmas!

(My corps, on the other hand, experienced a shortage of help in area restaurants that made getting a place to eat without a reservation difficult. Talk about inconvenient!)

While Lewis and Clark received visits from various local Indians almost daily, the logbooks often record the phrase “Not any occurences today worthy of notice,” which says a lot about the boredom they must have experienced in their cold, rainy 106 days there.

They were glad to leave on March 23. The movement of the elk herds and their overall discomfort caused them to pack up and head up back up the Columbia prior to the April 1 departure date originally set by the captains.

They knew leaving early could be a risk. They knew their success depended upon when the snow in the mountains melted. And nine days out on April 1, some Indians who resided at The Dalles in the Columbia gorge told them that they didn’t not expect the salmon to arrive until May 2, a bad sign for a group that had expected salmon to provide a significant source of food.

Lewis didn’t flinch. He wrote: “It was at once deemed inexpedient to await the arrival of the salmon as that would detain us so large a portion of the season that it is probable that we should not reach the United States before the ice would close the Missouri.”

In other words, like all weary travelers, they wanted to get home.