Anybody who has spent any time around Pete Rose has story they can tell you. He produced stories the way he produced hits. He is baseball’s all-time hits leader with 4,256. Memories of Pete cannot be so easily quantified, but there might be million of them. He was a story machine.

I covered Pete Rose as a player, as a manager and as a guy on the permanent suspended list who hawked pizzas, autographs, art prints and whatever else he could find to make a good living. The surprising news of his death last night at the age of 83 motivated me to tell one of the stories I often tell about him because it has touches on so many elements of Pete, both good and bad.

The year was 1973. I graduated from college in June and went to the work as a sportswriter for the Hamilton Journal-News. I had worked there the previous summer and covered a lot of Cincinnati Reds games (and high school games, Bengals games, Miami games and whatever else I could find), and I picked up on that in ‘73.

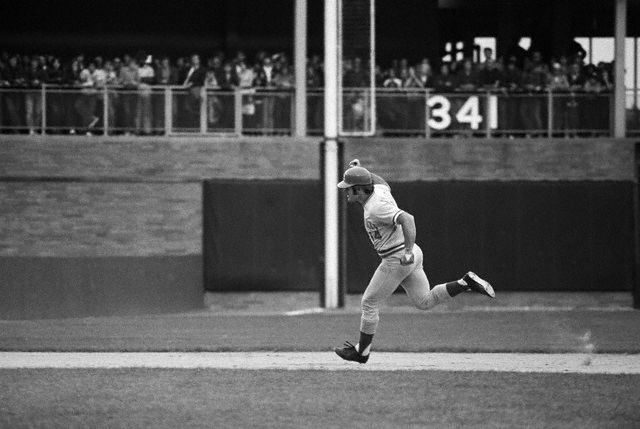

The Reds lost to the New York Mets in the National League playoffs, three games to two. But in Game 3 Pete went in hard to take out Mets shortstop Buddy Harrelson and break up a double-play and their fight started a bench-clearing brawl . Then in Game 4, when the Reds had to win to keep from being eliminated, Rose hit a home run in the 12th inning to help keep Cincinnati alive. As he rounded the bases in a booing Shea Stadium, Rose shook his fist at the fans, who had been cursing and heckling him, as opposing fans often did.

Cincinnati lost the fifth game and missed a chance to go to the World Series for the second consecutive year. But I asked my boss, sports editor Bill Moeller, what he thought about me trying to set up an off-season interview with Pete and ask him about his fist-shaking and the angry reaction he received from the New York fans.

Moeller told me to go ahead, so I set up an interview with Pete at his house in Oak Hills. I’m guessing this was late November or early December,

I got there a few minutes before seven when we had agreed to meet and no one was home. There were no lights in the house and no cars anywhere in sight. I was still waiting at about 7:15 when Pete pulled into the driveway and waved me over.

“Sorry I’m late,” he said. “I was at the race track.”

We went into his house. He showed me around, pointing out some of his trophies, and we were standing in kitchen talking when the phone rang. Pete answered, listened for a few seconds and scowled.

“I forgot,” he said.

He listened for a few seconds.

“I FORGOT,” he said.

Again, he stood there for a few seconds with his ear pressed to the phone.

“JESUS CHRIST, WHY DON’T YOU JUMP OFF A F—- BRIDGE BECAUSE I FORGOT TO PICK YOU UP?”

He slammed the phone and suddenly turned calm.

“That was Carolyn,” he said, of his first wife. “I was supposed to pick her and Petey up at her parents’ house.”

In an instant, he was back talking baseball, the Mets, New York and home run. The conversation went on for probably ten or fifteen minutes when Carolyn and Petey came through the door. She recognized me from the ballpark and said hello to me. She knew I was dating a pretty girl — my future wife — who worked at the ballpark whom she also knew, having talked to her occasionally in the tunnel outside the clubhouse.

“Bob, whatever you do, don’t ever get married.”

I think she was kidding, but who knows? I knew the girl sometimes talked to Carolyn and I briefly wondered if Pete’s wife would have the same advice for her.

The conversation moved on. We were in the family room now – I guess it was the family room – and Petey was in and out of the room. Pete suddenly stopped what he had been saying and focused on his four-year-old son.

“Petey can hit them over the house,” Pete said.

I started to say something intelligent like “really?” but Pete beat me to the punch.

“Can’t he, Carolyn? Can’t Petey hit them over the house.?”

Carolyn looked disgusted. She nodded, uttered a couple of weak “yeahs” and walked into another room.

Pete grinned. “C’mon, I’ll show you.”

It’s dark and cold outside. I’m thinking 30 degrees, but it may have been 35 or 40. Regardless of the actual temperature, this was the first point of the evening where I was actually surprised.

Pete flipped on the backyard lights, motioned for Petey to grab his bat, grabbed a few plastic baseballs and marched out the door with Petey and me behind him.

Petey took his place – he knew exactly where to stand – and Pete threw him a pitch. It looked like a fat pitch, but Petey swung and missed.

“C’mon!” Pete said.

I suppressed a smile. Pete threw another fat pitch. Petey missed again. The expression on Pete’s face turned to the same scowl had seen when he on the telephone with Carolyn.

“C’mon, Petey!” He looked at me. “This has never happened before.”

I swallowed another smile, which was probably easier than you’d think because I was getting pretty cold standing out there with no jacket on.

Pete threw another one and Petey swung like his happy childhood depended on it and drove the ball over the roof of the two-story house.

Pete beamed. “See, I told you he could hit them over the house.”

Pete waved Petey in, and our little jacketless parade followed the future hit king into the warm outfield fence, er, house.

“Petey plays because he loves it,” Pete said. “I don’t push him at all.”

I don’t doubt for a minute that Petey loved it – he became a pretty good player in his own right and actually played 11 games for the Reds in 1997. But it was impossible not to recognize the intensity that Pete had for his son playing as the same intensity that he had into making himself into a Hall of Fame player if not a Hall of Fame human.

“When he goes to high school, he’s going to go to Elder,” Pete said. “He’s not going to Western Hills.”

I almost laughed out loud at that line. Pete went to Western Hills, the public school on the city’s west side. Elder was the west side’s parochial powerhouse, which won state championships almost as a matter of course. Pete had a funny way of not pushing him – at age four.

And then again, if you knew him, it’s hard not to think about this as Pete simply being Pete. Pete wanted this as bad for Petey as he had wanted it for himself, and given his own experience as a self-made superstar, he probably believed that a long, lucrative major-league baseball could be achieved by anybody who was willing play every second as if their life depended upon it.

Problem is, few people have ever played baseball as hard or as intensely as Pete Rose.